It’s pretty easy to remain keenly aware that the wastewater we treat is from toilets, sinks and, again, toilets. But there are all kinds of other wastewater in that odoriferous mix, including from industrial sources. The District’s Industrial Pretreatment program helps do the “upstream” work with area industries to keep industrial pollutants out of their wastewater before it arrives at our treatment plant. Not only is this good for protecting the plant’s biological treatment processes and the surface waters we discharge treated effluent to, but having a pretreatment program is required by law.

National standards, locally enforced

The federal Clean Water Act requires that states administer a wastewater pretreatment program for industrial facilities that discharge wastewater into a municipal system. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines categories of industries to monitor and what pollutants should be regulated. In Wisconsin, the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) passes on most of the regulatory responsibility to municipal treatment plants by requiring them to have their own industrial pretreatment program.

“The DNR tells us that to be in compliance with our own permit, we have to regulate industries that are discharging to us,” says Julie Maas, the District’s pretreatment coordinator. “We are essentially acting as an agent of the DNR and EPA, administering those regulations to our industries.”

Deciding who and what should be monitored

How do we determine what industries need to be regulated? Julie explains that any facility that’s a Significant Industrial User (SIU) needs to be evaluated to determine whether a permit is needed. A facility is considered an SIU if it discharges 25,000 gallons or more of wastewater per day, its wastewater contains high organic loadings, its industry is defined as a categorical user by the EPA, or its wastewater has reasonable potential to cause harm. Metal finishers, steam-generated power plants, and pesticide and pharmaceutical manufacturers are examples of categorical users.

“If you’re in a business that does work that’s defined under a category by the EPA, you’re probably generating wastewater that contains pollutants,” says Julie.

Julie says that District staff judgment is also used to decide whether a business is regulated. For example, since the pretreatment regulations were written by the EPA decades ago, they might not include newer contaminants or industries like biotech. “We also might want to look at a contaminant we are particularly concerned about, like chloride,” says Julie.

There are also tests for contaminants that aren’t directly connected to limits in our permit but are linked to our permit-required toxicity testing. “A lot of the VOCs and other parameters we test for could cause toxicity or stress to our plant bugs or to fish in our receiving streams,” says Julie. “We can issue a permit to anyone we want to keep tabs on, but we also don’t want to unnecessarily burden anyone with regulation.”

Executing the program

As the pretreatment coordinator, Julie writes an individual permit for each facility, using EPA guidance and our own sewer use ordinance to define limits for contaminants. Currently, the District has 19 permitted facilities. Wastewater is sampled four times per year to ensure the facilities are in compliance with their permits: two self-monitoring reports are submitted by the permittees, and two on-site sample events are conducted by District staff per year.

“This is a large staff effort to support our permit because it requires the assistance and coordination of three groups working together – Pretreatment, Collection System Services and Laboratory Services,” says Martye Griffin, director of ecosystem services.

production line at Graber Manufacturing.

Making it happen: sampling weeks

The on-site industrial pretreatment (IP) sampling occurs during one week in the spring and again in the fall. It starts with a lot of communication and scheduling work, done by Ray Schneider, Collection System Services (CSS) supervisor. “I do a lot of phone work,” says Ray. “It needs to be scheduled with their needs at the facilities and our other regular work and paced for the lab so all the samples aren’t coming in at once to them.”

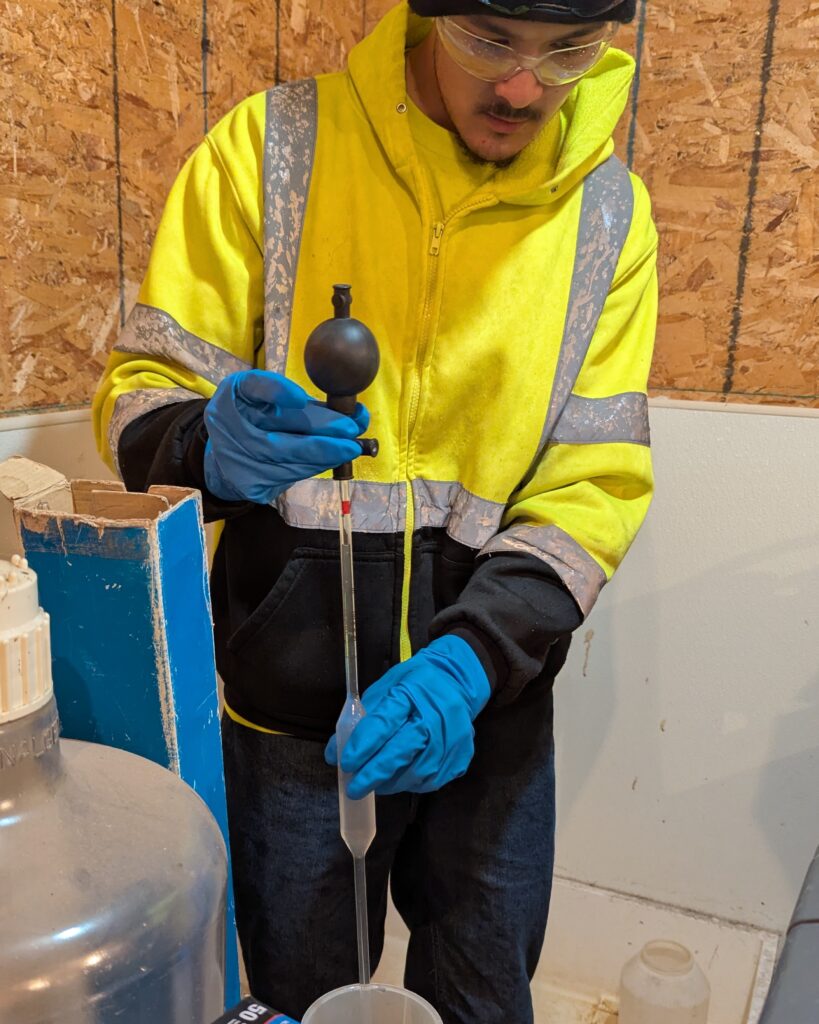

Out in the field, CSS staff have a variety of sample collection environments. Some samples are taken outside a facility in a manhole, while others require them to enter a facility and follow the safety protocols of that particular industry. When a composite sample is required, a sampler needs to be set up a few days before the day of collection.

“It’s a complicated scheduling effort and Ray has it down to an art form,” says Julie. “Our CSS team has really good relationships with the facilities and a good reputation for communicating and working safely and carefully.”

Meanwhile, back at the lab…

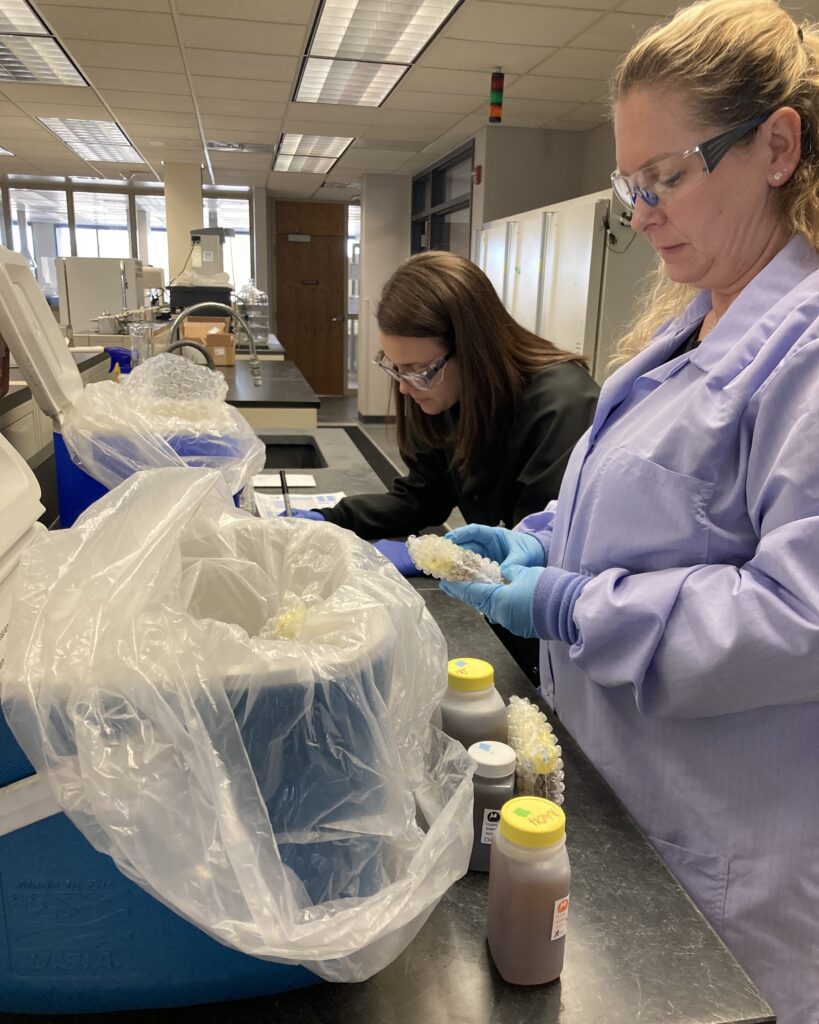

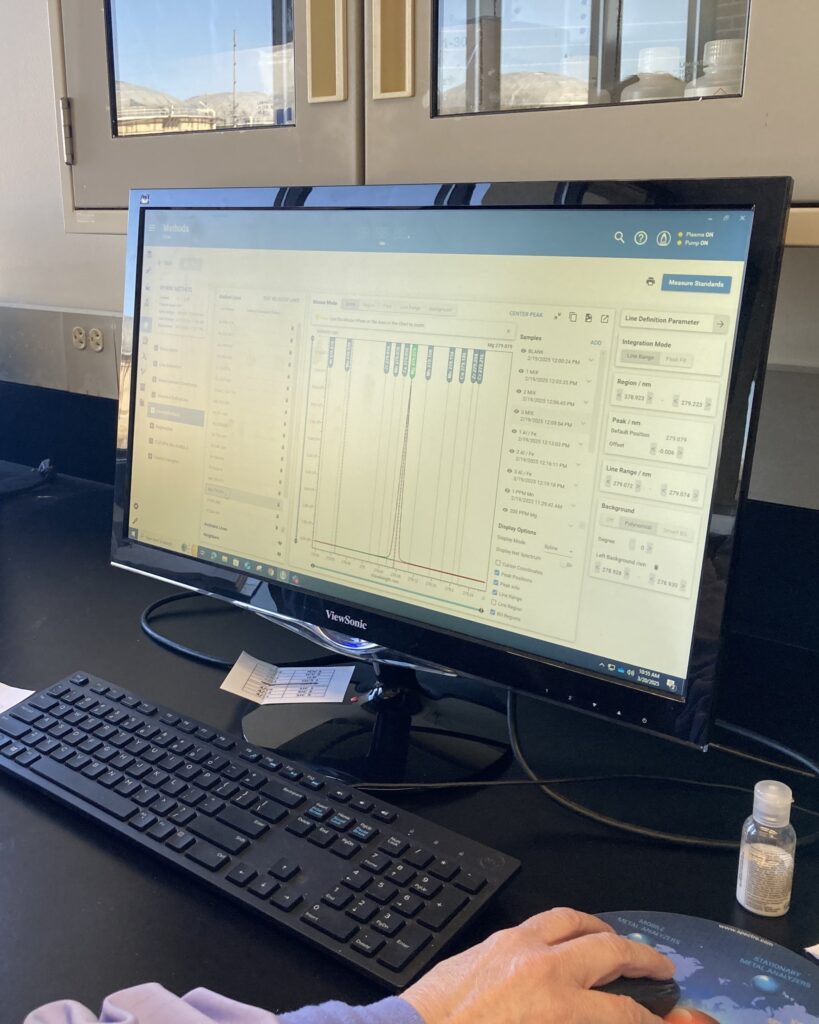

Chemist Kris Mazzuca provides a lot of lab support during the industrial pretreatment (IP) sampling events. This is because she conducts testing for metals, for which all of the IP samples need to be analyzed. First, Kris preps, labels and organizes all the sampling collection supplies so that CSS can come in and grab them on their way to a facility during the sampling week. Once the samples start coming back that week, things get busy. “It’s a lot more samples at once than we normally see and there are so many different parameters compared with our normal sample analysis,” says Kris.

To throw one more moving part into this effort, there are parameters the District lab is not certified to analyze, so some samples are sent to a contracted lab. These need to be coordinated and timed carefully, as some need to be analyzed quickly before they break down. CSS staff collect these samples under time pressure and return them to the lab for receiving, packing in coolers and sending them off for overnight delivery. “The rush is to be prepared for the courier because we don’t know exactly when they will arrive,” says Mary Powers, lab manager, who steps in to help Kris when needed.

It’s a relationship

As new industries establish themselves in the District’s service area, our industrial pretreatment program will have to grow to stay in compliance with our own permit. Julie describes the relationship with our current 19 permitted industries as friendly, cooperative and collaborative. Having long-time staff members like Ray and Mike Kressin, CSS lead, to work with facility staff also helps build good relationships, and the high-caliber work of lab staff like Kris maintains the integrity and effectiveness of the program.

Julie is hopeful that new industries will be receptive to a positive relationship as well. “The District’s approach, which is consistent with my philosophy, is very much to build partnerships,” says Julie. “We want them to succeed and also to make sure we are all meeting our requirements. All of our permittees seem genuinely like they want to do the right thing.”

Article and photos by Jessica Spiegel