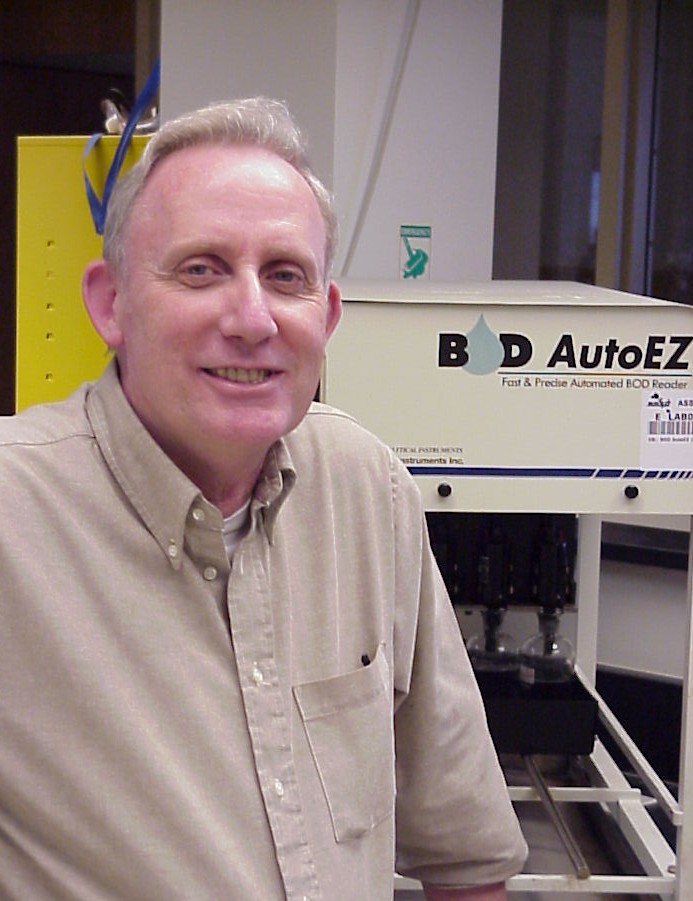

One of the District’s most interesting employees was Greg Zelinka. Greg began his 33-year career in 1970 as a chemist in the laboratory. Greg had a keen sense of curiosity and was always looking for ways to improve any area of the District. He was not satisfied to just perform the standard lab tests. Developing ways to automate processes to save time and money was a love of Greg’s. Read how he became the District’s inventor extraordinaire, particularly for his patented invention, the BOD Auto EZ.

A way to measure chlorine application rate

In the early 1970s, the District was using chlorine to disinfect the plant’s effluent. At that time, the lab was located on the second floor of what is now Shop One, the chlorination equipment was located on the first floor, and right next door was the operators’ control room. As the operators manually changed the pumping capacity of the effluent pumps, they also had to change the rate at which chlorine was applied. The operators, however, had no way of knowing if their adjustments were adequate.

Seeing this problem, Greg decided to develop an online analyzer that would continually measure the chlorine residual in the effluent. By mounting his analyzer in the control room, the operators could always see the result of their adjustments.

Inventing a sampler

Another issue the operators dealt with was the collection of samples from around the plant. One of the operators, known as the “legman,” would walk through the plant with a dipper and a kit holding a number of bottles. Each hour they would collect samples from various locations in the treatment process and bring them back to the control room. One of these samples was of the wastewater coming into the plant. There were four force mains bringing wastewater to the plant. Greg knew that if samples of each force main could be collected separately, the lab could learn a lot about the wastewater coming from the different parts of the collection system.

To solve this problem, Greg tapped each of the force mains in the building known as the Filter Lift Building and connected them to individual samplers that he built. Because the 24-hour samples that were collected needed to be proportionate to the flow, Greg also connected his samplers to the venturi meters that measured the flow of wastewater through each of the force mains. Greg’s design was years ahead of any commercial sampler design.

Measuring dissolved oxygen levels to save energy

Perhaps the biggest use of energy at the treatment plant in the 1970s was for the blowers that provided air to the aeration tanks. Knowing how much dissolved oxygen (DO) was in the aeration tanks at any time was critical to providing adequate oxygen to the biological culture in the tanks without wasting energy by pumping in excessive air. The “legman” could use a portable probe to measure the DO level, but those measurements were time-consuming and not done routinely.

To address this problem, Greg built a probe that could be mounted permanently in an aeration tank and could continually measure the DO concentration. He routed this information back to a strip-chart recorder in the operators’ control room. This allowed the operators to see the dissolved oxygen concentration, monitor the concentration trend, and decide to turn blowers on and off to meet the DO needs of the system. Monitoring the dissolved oxygen concentration in aeration tanks is now an industry standard.

Expanding the lab’s analyses capabilities

In the early 1980s, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were found in some of the sludge that was stored in the District’s sludge lagoons, east of the treatment plant. This was a problem because there was a limit on the concentration of PCBs that could be contained in biosolids that were applied to farmland through the District’s Metrogro program.

It became clear that the District was going to need to perform many PCB analyses while a solution to this problem was developed. Unfortunately, there were very few labs that were capable of measuring PCBs and even fewer that could measure them in biosolids. By this time Greg was the laboratory manager. Within a short time, Greg, along with lab chemist Mark Anderson, developed a method to accurately measure PCBs. This was crucial to continuing the Metrogro program and rehabilitating the lagoons, which had become a Superfund site because of the PCBs.

The patented invention

As laboratory manager, Greg was well aware of the amount of time that the District’s chemists needed to spend to measure the biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) in a wide range of samples each day. He thought there must be a way to automate this process. This led to his most famous invention, the BOD AutoEZ.

Over many hours in the basement of his house, Greg designed and built a device that could hold 24 BOD bottles, measure the amount of oxygen in four bottles at the same time, automatically move to the next set of four bottles, transfer the dissolved oxygen information into a computer, and calculate the BOD value for each bottle. This significantly reduced the amount of time spent on this analysis.

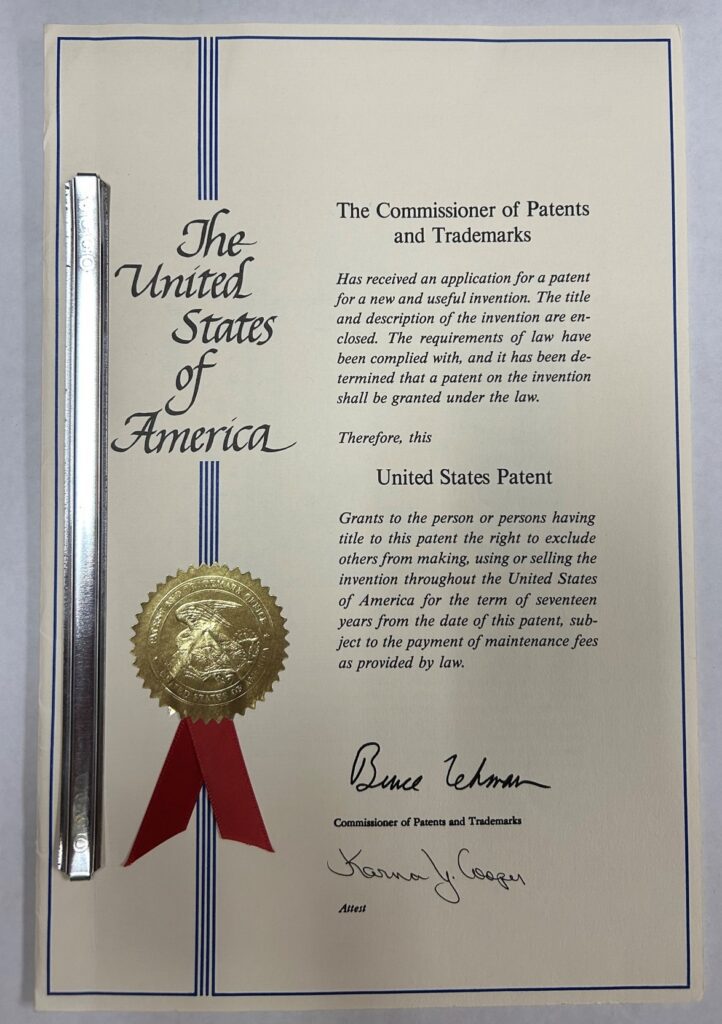

Seeing the value of this device to the wastewater industry, Greg and the District patented the BOD AutoEZ. Eventually, the patent was sold to a commercial manufacturer. BOD AutoEZs are now found in laboratories throughout the U.S. and in some foreign countries as well.

Innovating right up to retirement

One of the last projects Greg worked on before he retired dealt with odor control. Odors were prevalent at a couple of the pumping stations. Greg first worked to identify the constituents that were causing the odors and then developed systems to control them.

Early odor control systems had been mixtures of wood chips and dried biosolids. Although successful in removing odors, the woodchips would eventually decompose and need to be replaced. To address this issue, Greg experimented with using lava rocks and other inert substances as the support media in the odor control beds.

In addition to the constant experimental and innovative work Greg did, he also stayed up to date with the latest developments in laboratory instruments. Besides inventing hardware, Greg also became a computer expert. This led to his development of a computerized laboratory information management system at a time when such systems were first being developed commercially.

The activities of the District’s “Inventor Extraordinaire” kept the District at the forefront of new ideas in the wastewater industry.

Visit the History section of our blog for additional articles documenting the early years of wastewater treatment in the Madison area.

Written by Paul Nehm