As long as we’ve had wastewater treatment technology in the Madison-area, we’ve needed effective ways to handle, treat and dispose of biosolids and sludge.

When both the Burke Wastewater Treatment Plant (1914) and the Nine Springs Wastewater Treatment Plant (1928) were built, solids in the wastewater were separated by gravity. At the Burke Plant, this occurred in a fairly complicated design in which settled solids from sludge separators flowed by gravity into sludge digesters. At the Nine Springs Plant, Imhoff Tanks were used for biosolids separation. These tanks had a slot in the mid-level of the tanks that allowed solids to fall into the bottom of the tanks where they could digest. These digestion compartments at both plants were not heated nor mixed as today’s high-rate digesters are.

Drying and managing the solids

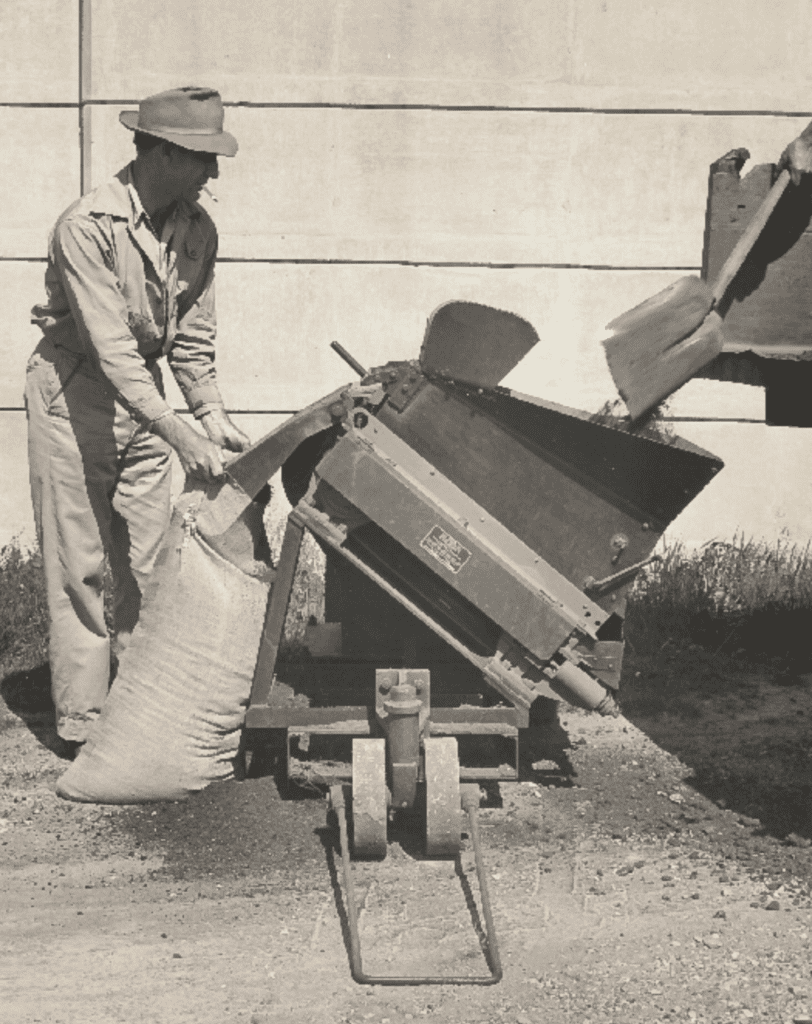

Periodically, the digested solids were removed from the digestion compartments and placed in sludge lagoons and sludge drying beds. It’s believed that the sludge lagoons were used to store sludge before it was placed on the drying beds. While the drying beds at the Burke Plant had 18 inches of sand laid on fine gravel on a plank floor, the drying beds at the Nine Springs Plant had only six inches of sand over 30 inches of gravel. The drying beds at both plants had drain tile under the sand to carry away water. Both plants also had railroad tracks down the center of each bed. This allowed a small engine to pull cars along the drying beds. Workers would then fork or shovel the dried sludge into the cars.

Early days of “Nitrohumus”

Records from the Burke Plant indicate that the dried sludge was spread on “adjacent swamp land.” At the Nine Springs Plant, attempts were made to use dried sludge as a resource. For instance, in November of 1933, the City of Madison requested that the District supply some sludge to be used at Breese Stevens Field. Later, in 1944, the Madison Community Union requested that 154 tons of sludge be furnished free of charge to the Victory Garden Committee.

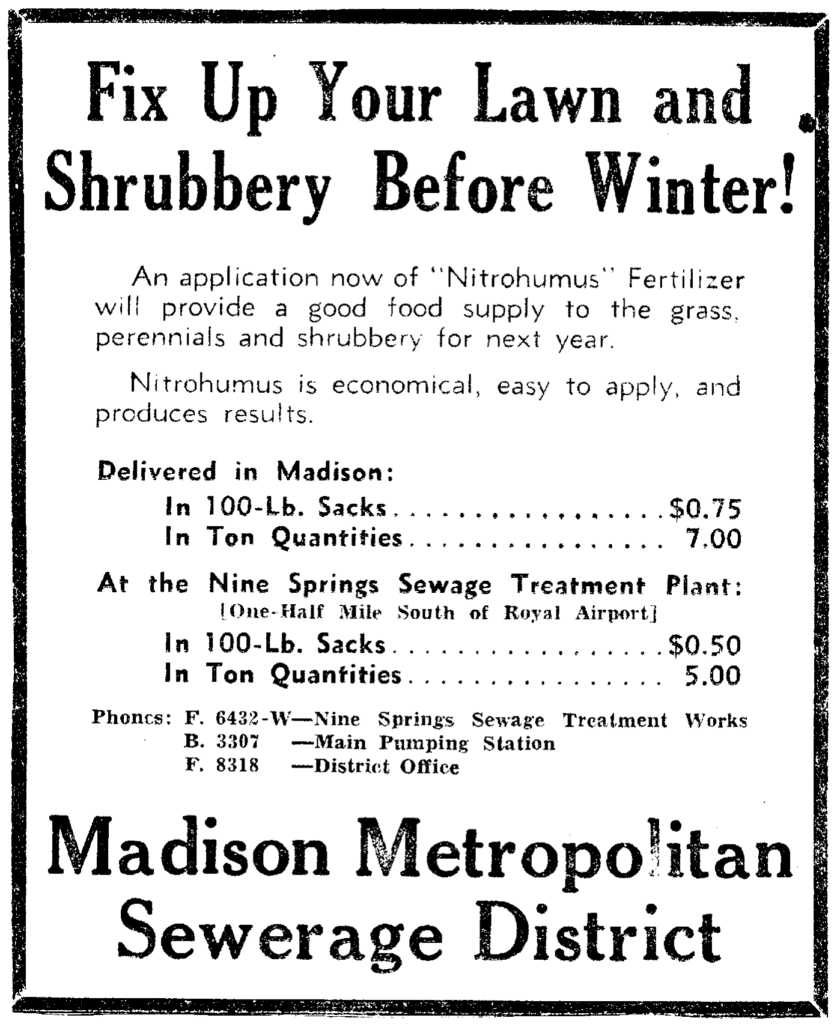

With the construction of the First Addition to the Nine Springs Plant in 1939, a room in the Service Building was used to grind some of the dried sludge to make a more uniform product. The District applied the name “Nitrohumus” to this material and made it available to the general public. As the newspaper ad states, the material was available in bags or bulk quantities. Users could either come to the treatment plant to pick it up or they could request delivery for a higher price.

Heavy rains force looking at alternatives to drying sludge

During the summer and fall of 1940, heavy rains retarded the drying of sludge on the drying beds. This resulted in the District not being able to remove the necessary amount of sludge from the digesters at the Nine Springs plant that winter. Rains continued to hamper drying in the spring of 1941.

That summer, Chief Engineer Lord recommended to the Commissioners that a pipeline be laid across what was then known as Raywood Road to the marsh area to the east of the road. The thought was that the liquid in the sludge would seep away or evaporate while in the marsh. Mr. Lord noted that the embankments that were around the area would be adequate to contain the sludge. However, by 1945 the District had to construct an embankment on the south side of the marsh to provide more storage.

Lagoon containment areas established, but…

Building additional dikes in the marsh and raising the dike elevations continued through the 1950s and 1960s. The containment areas eventually became known as Lagoon 1 (the west lagoon) and Lagoon 2 (the east lagoon). During this time, the District continued to make dried sludge available to the general public, but the majority of the digested sludge was sent to the lagoons. By the late 1960s, maintaining the height of the dikes became increasingly difficult as the dikes seemed to sink under the weight of the material used to construct them.

… the dikes only hold for so long

Disaster finally struck when on April 9, 1970, a section of the north dike settled, allowing about 40 acre-feet of supernatant to escape the lagoons and flow into the drainage channel around the lagoons. Although repairs were made the next day, the same section of dike again settled on April 12. With this event, most of the liquid in Lagoon 2 flowed into Nine Springs Creek.

It is interesting to note that in 1949 the Salvage Engineering Corporation of Madison offered to purchase the District’s sludge for fertilizer processing. They requested exclusive rights to the sludge and would pay the District 10% of the profits. Mr. Lord and the Commissioners decided not to pursue this offer. One can only wonder if this offer had been accepted, would the sludge lagoon problems ever have existed?

Watch for the next article in the series, “Development of the Metrogro program.” Visit the History section of our blog for additional articles documenting the early years of wastewater treatment in the Madison area.

Written by Paul Nehm