Setting the course for responsible wastewater management

The history of Madison area’s wastewater management efforts dates back to the late 1880s, when 18 districts around Madison were served by public sewers that discharged sewage into lakes Mendota and Monona. While this provided a new convenience, citizens quickly expressed their concern about discharging raw sewage into their beautiful local lakes. As a result, the city authorized the first sewage treatment plant in 1895, nearly 50 years before most other communities had such a facility.

The first plant in District history, which used a chemical precipitation process, went online in May 1898, but it was abandoned in January 1901 when it was determined the technology it used produced effluent (cleaned water discharged back to nature) that was unsatisfactory. This plant was replaced by a septic tank and cinder plant located near the Yahara River. With the growth of Madison, this plant became overloaded and was replaced in 1914 with the Burke Plant on Madison’s north side, which is credited as being the first trickling filter plant in history of the United States.

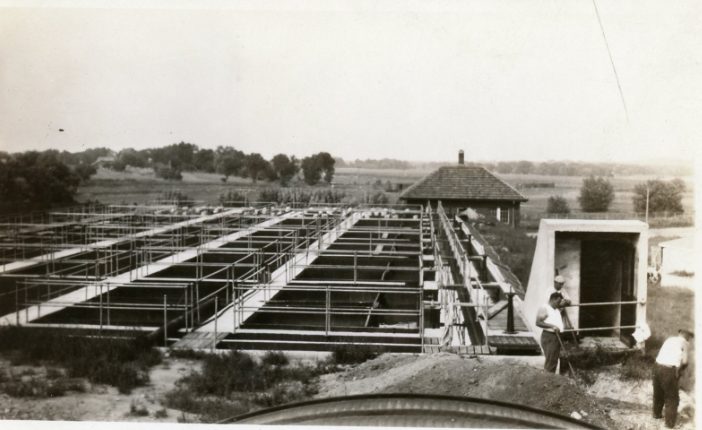

As the city continued growing, it became apparent that an additional sewage treatment plant was needed. By 1928, the Nine Springs Wastewater Treatment Plant, the current home of the District’s operations, was up and running with a capacity of 5 million gallons per day (MGD).

Madison’s sewage treatment capacity quickly grew to 10 MGD between the Nine Springs and the Burke treatment plants. Driven by growth in surrounding communities and a rally cry for a more unified, metropolitan approach to sewage collection and treatment, Madison Metropolitan Sewerage District was established in Dane County Court as a municipal corporation on February 8, 1930. The District is one of the oldest regional sewer utilities in the United States.

Growing with our communities

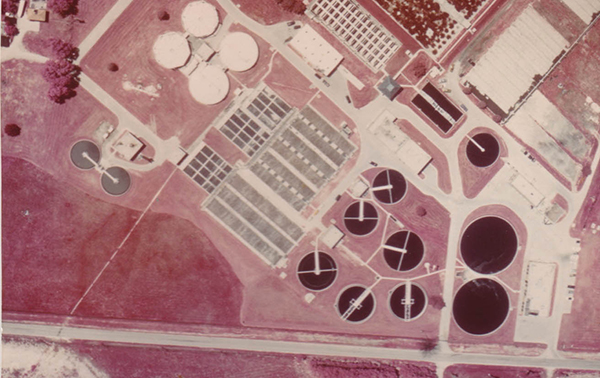

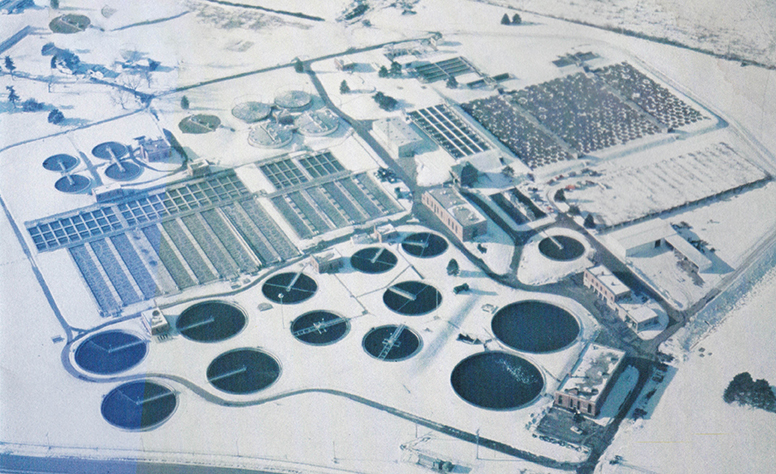

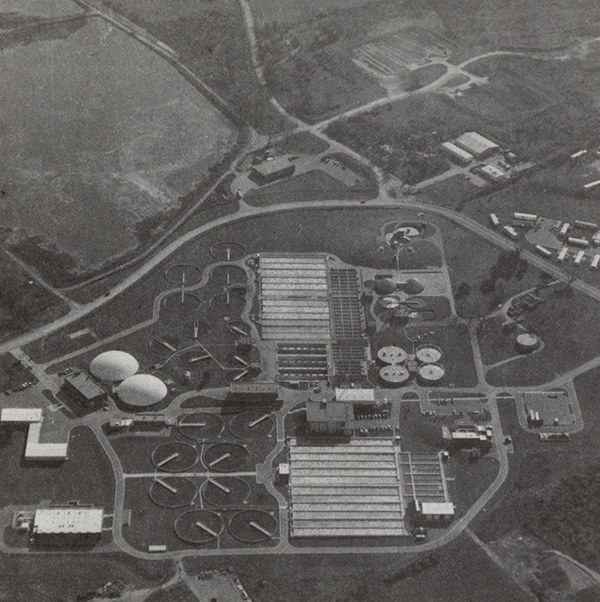

The footprint of the District’s treatment plant as well as its collection service has grown through history as local communities have grown.

The first addition to the Nine Springs plant was completed in 1936. This addition increased the treatment capacity, which allowed for the Burke Plant to be taken offline. To date, the plant has gone through 11 additions to increase treatment capacity; improve solids processing, handling and recycling; and incorporate new technology and innovation into the plant.

Effluent from the Nine Springs treatment plant was discharged into the Madison lakes until the 1950s, when a state law was passed prohibiting discharge into Madison lakes. To accommodate this change, the District decided to route cleaned wastewater to Badfish Creek. With the addition of Verona to our service area, the District built infrastructure in the 1990s to also discharge effluent to Badger Mill Creek, near Verona, to maintain the balance of water between the Sugar River watershed and the Yahara River watershed.

Today, the District serves about 435,000 people in 24 Madison-area customer communities covering about 190 square miles across Dane County. The District owns and operates 150 miles of pipe and 18 regional pumping stations that convey approximately 37 million gallons of wastewater to the Nine Springs Wastewater Treatment Plant daily. To put that into context, if wastewater came to the plant via semi-trailer, a truck would come through the gates every 11 seconds.

Sustainability, innovation and adaptability

Like their predecessors in history, District staff today are dedicated to protecting public health and the environment. They are a passionate and experienced resource recovery team who fulfill the District’s mission not only by responsibly treating wastewater, but doing so through sustainable, adaptable and innovative methods.

For instance, the District has taken a pioneering, multi-pronged approach to reducing phosphorus in local waterways. Phosphorus is a valuable resource found in fertilizer and is required to help plants grow, but too much phosphorus can cause dangerous and unsightly algae blooms in our waterways. In 1999, the District modified its biological treatment processes to remove most phosphorus from the wastewater, and in 2014, took that to the next level by installing cutting-edge technology to harvest struvite, a form of phosphorus, from wastewater to produce a valuable fertilizer product. The District is also a leader in adaptive watershed management through Yahara WINS, a collaborative effort among municipalities, farmers, landowners and others to implement land-based practices to reduce the amount of phosphorus entering local waterways.

District staff are setting the pace for reducing salt pollution in local waterways through innovative public outreach and education activities. The District is also a member of Wisconsin Salt Wise, a coalition of organizations working together to reduce salt pollution in our lakes, streams and drinking water.

The history section of our blog offers in-depth stories on the creation of the District, our early years of service and other interesting narratives from the past.

View history blog articles.

Original Plant

The original plant included Imhoff tanks, two parallel trickling filters, two clarifiers, sludge drying beds and an administrative building.

First Addition

To accommodate the need for more treatment capacity, the First Addition included facilities for grease and grit removal; an additional clarifier following the trickling filters; two primary tanks; four aeration tanks; three additional clarifiers; two digesters; two sludge storage tanks; and four additional buildings. These additions allowed the District to use the new activated sludge process for wastewater treatment and separate digestion of biosolids.

Second Addition

With the need for more treatment facilities, the Second Addition in the District’s history added two primary tanks; two aeration tanks; and one clarifier; and one digester; a sludge thickener; sludge drying beds; and sludge lagoons.

Third Addition

This addition included a grit chamber, primary tank, two aeration tanks, a clarifier and an additional building.

Effluent Discharge

The District’s discharge point was changed to send effluent, or cleaned wastewater, to Badfish Creek. Previously in history, treated water was discharged upstream of Lake Waubesa. Two effluent storage tanks and a new pumphouse were built to direct water to the new discharge point.

Fourth Addition

This addition was needed to increase the plant’s treatment capacity yet again and included grit tanks, influent meters, three primary tanks, one aeration tank, two clarifiers, two sludge thickeners and three additional buildings.

Fifth Addition

With a growing service area and population, further treatment capacity was needed. The Fifth Addition included eight more primary tanks; six aeration tanks; four clarifiers; two sludge thickeners; a diversion structure; and two buildings. This addition also moved Raywood Road to accommodate campus expansion.

Sixth Addition

The Sixth Addition added three digesters and a control building for solids handling and recycling, and the first Metrogro trucks and applicators were purchased. The Operations Building and Vehicle Loading Building, which houses Metrogro, were also built. A few years later, two gravity thickeners were converted to dissolved air flotation thickeners as part of this addition and a gravity belt thickener building was built to thickened digester sludge.

Seventh Addition

Driven by changes in ammonia regulations throughout history, the Seventh Addition resulted in the doubling of the size of the treatment plant. This included the addition of three aeration tanks and one clarifier in the East Plant and replacement of the trickling filters with five primary tanks, twelve aeration tanks, and eight clarifiers.

The effluent chlorination system was replaced with an ultraviolet (UV) disinfection system. A new effluent pumphouse was built to house the UV system and the new effluent pumps while the existing effluent pumphouse was converted to a maintenance facility. To increase the efficiency of the treatment process, a computerized process control system was installed.

Eight Addition

Driven by a need to end the use of the sludge lagoons for biosolids storage, the Eighth Addition included three Metrogro storage tanks, Metrogro pump station, odor control beds, and an addition to the Vehicle Loading Building. The Operations Building was expanded and other buildings were constructed, including Septage Receiving.

Badger Mill Creek Discharge

Adding Verona to the District’s service area required the addition of two effluent pumps and the construction of a 10-mile forcemain to Badger Mill Creek to return effluent to the Sugar River watershed.

Ninth Addition

Changes in phosphorus regulations for effluent required aeration tank modifications for biological phosphorus removal. In this addition, the District also replaced its UV system and upgraded control systems.

Tenth Addition

To diversify the District’s biosolids product, the Tenth Addition added a digester, converted a storage tank to a digester, and added a centrifuge and biosolids storage building. The Headworks building with septage receiving, and influent screening along with new grit removal tanks was also built.

Eleventh Addition

The primary goal of the Eleventh Addition was to improve the District’s solids handling processes by adding two more digesters and a control building. This project also gave the District the capability to recover phosphorus in the form of struvite from wastewater.

Maintenance Facility

The District unveiled its new Maintenance Facility in 2016, the first building on campus to be LEED certified. The building was constructed to provide more space and better working conditions for several Maintenance workgroups. To see some of the green and sustainable features incorporated into the design, check out our LEED Platinum virtual tour.

Shop One Renovations

Prior to completion of the new Maintenance Facility in 2016, Shop One housed mechanical, electrical, sewer maintenance and monitoring functions. In 2019, interior renovations of the Shop One building made the space functional for meetings and tour groups. View the history of the Shop One building.